Lesson 12: Reusing Code With Functions

ClojureScript is a functional programming language. The functional programming paradigm gives us superpowers, but - love it or hate it - it also makes certain demands on the way that we write code. We have already discussed some of the implications of functional code (immutable data, minimizing side effects, etc.), but up to this point we have not studied what a functions are - much less how to use them idiomatically. In this lesson, we define what functions are in ClojureScript, and we will study how to define and use them. Finally, we’ll look at some best practices for when to break code into separate functions and how to use a special class of function that is encountered often in ClojureScript - the recursive function.

In this lesson:

- Learn ClojureScript’s most fundamental programming construct

- Write beautiful code by extracting common code into functions

- Solve common problems using recursion

Understanding Functions

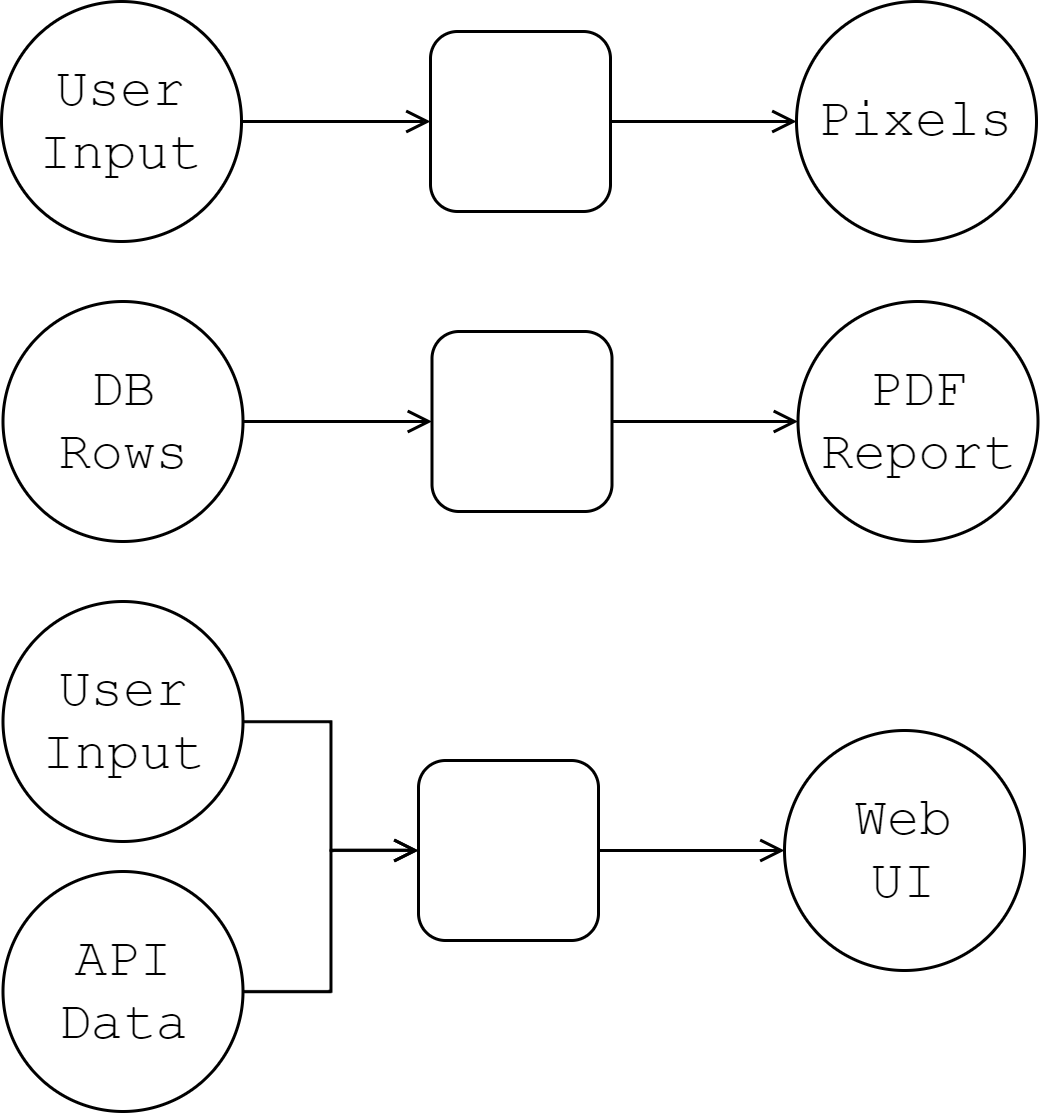

Think about the programs that you have written in the past. Maybe you primarily write enterprise software. Maybe you write games. Maybe you’re a designer who creates amazing experiences on the web. There are so many different types of programs out there, but we can boil them all down to one common idea: a program is something that takes some sort of input as data and produces some sort of output. Enterprise software usually takes forms and generates database rows, or it takes database rows and generates some sort of user interface. Games take mouse movements, key presses, and data about a virtual environment and generate descriptions of pixels and sound waves. Interactive web pages also take user input and generate markup and styles.

Programs transform data

In each of these cases, a program transforms one or more pieces of data into some other piece of data. Functions are the building blocks that describe these data transformations. Functions can be composed out of other functions to build more useful, higher-level transformations.

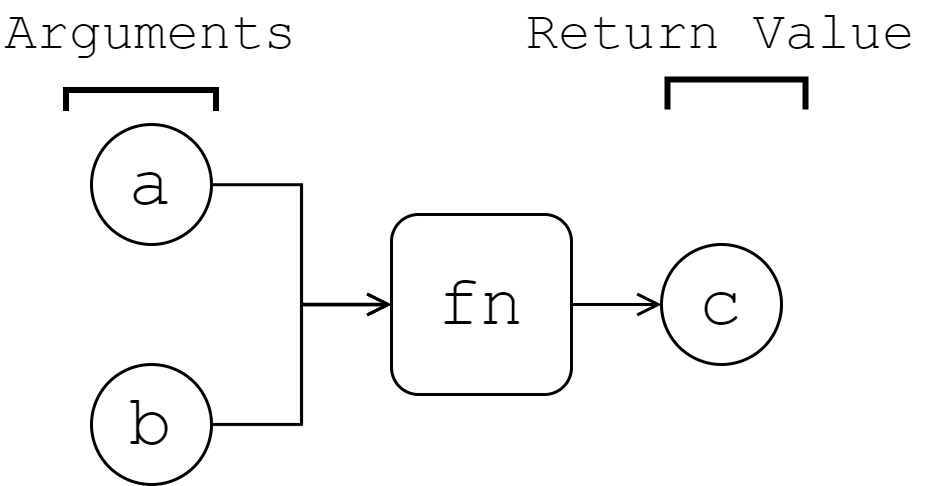

We can think about functional programming as a description of data in motion. Unlike imperative code that makes us think about algorithms in terms of statements that assign and mutate data, we can think of our code as a description of how data flows through our program. Functions are the key to writing such declarative programs. Each function has zero or more input values (argument), and they always return some output value1.

Functions map input to output

Defining and Calling Functions

Just like strings, numbers, and keywords, ClojureScript functions are values. This means that they can be assigned to vars, passed into other functions as arguments, and returned from other functions. This should not be a new concept for JavaScript programmers, since JavaScript functions are also first-class values:

const removeBy = (pred) => { // <1>

return list => // <2>

list.reduce((acc, elem) => {

if (pred(elem)) {

return acc;

}

return acc.concat([elem]);

}, []);

}

const removeReds = removeBy( // <3>

product => product.color === 'Red'

);

removeReds([

{ sku: '99734N', color: 'Blue' },

{ sku: '99294N', color: 'Red' },

{ sku: '11420Z', color: 'Green' },

]);

- Assign a function to a variable,

removeBy - Return a function

- Pass a function as an argument to another function

A direct translation2 of this code to ClojureScript is pleasantly straightforward:

(def remove-by ;; <1>

(fn [pred]

(fn [list] ;; <2>

(reduce (fn [acc elem]

(if (pred elem) acc (conj acc elem)))

[]

list))))

(def remove-reds ;; <3>

(remove-by (fn [product] (= "Red" (:color product)))))

(remove-reds

[{:sku "99734N" :color "Blue"}

{:sku "99294N" :color "Red"}

{:sku "11420Z" :color "Green"}])

- Assign a function to a variable,

remove-by - Return a function

- Pass a function as an argument to another function

Since JavaScript was designed with a lot of the features of Scheme - another Lisp - in mind, it should come as no surprise that functions work similarly across both languages. The primary differences are syntactical rather than semantic. So with that, let’s take a look at the syntax for defining functions.

fn and defn

Functions may be defined with the fn special form. In its most basic version fn takes a vector of parameters and one or more expressions to evaluate. When the function is called, the arguments that it is called with will be bound to the names of the parameters, and the body of the function will be evaluated. The function will evaluate to the the value of the last expression in its body. As an example, let’s take a function that checks whether one sequence contains every element in a second sequence:

(fn [xs test-elems] ;; <1>

(println "Checking whether" xs ;; <2>

"contains each of" test-elems)

(let [xs-set (into #{} xs)] ;; <3>

(every? xs-set test-elems)))

- Declare a function that takes 2 parameters

- The first expression is evaluated for side effects, and its result is discarded

- The entire function takes on the value of the last expression

This example illustrates the basic form of fn where there is a parameter vector and a body consisting of 2 expressions. Note that the first expression logs some debug information and does not evaluate to any meaningful value. The function itself takes on the value of the final expression where xs and test-elems are substituted with the actual values with which the function is called:

(let [xs-set (into #{} xs)]

(every? xs-set test-elems))

Anonymous Function Shorthand

There is another even terser syntax for anonymous functions that saves a few keystrokes

by omitting the fn and the named argument list. In the next example, we use this

abbreviated syntax.

#(let [xs-set (into #{} %1)]

(every? xs-set %2)))

As we can see, the function itself is defined with #(...), and each argument is referred to by its position - %1, %2, etc. If the function takes only 1 argument, then the argument may be referred to simply as %:

(#(str "Hello " %) "world")

;; => "Hello world"

While this syntax is handy, we should only use it for extremely small functions whose intent is readily apparent. In the normal case, we should prefer to use the slightly longer syntax for the clarity that comes with named arguments. Also, for a function that takes more than one argument, this syntax usually introduces more confusion than necessary. It is still fairly common in ClojureScript code and is often used for event callbacks.

Defining Named Functions

You may have noticed that while we have declared a useful function, we do not have any way to call it because it lacks a name. This is where defn comes in - it is a shorthand for declaring a function and binding it to a var at the same time:

(def contains-every? ;; <1>

(fn [xs test-elems]

;; function body...

))

(defn contains-every? [xs test-elems] ;; <2>

;; function body...

)

- Bind the anonymous function to a var,

contains-every? - Define the function and bind it at the same time with

defn

As we can see, defn is a useful shorthand when we want to create a named function.

In order to keep our programs clean, we usually group related functions together into a namespace. When we bind a function to a var using either def or defn, the function becomes public and can be required from any other namespace. In ClojureScript, vars are exported by default unless explicitly made private3. Unlike object-oriented programming, which seeks to hide all but the highest-level implementation, Clojure is about visibility and composing small functions - often from different namespaces. We will look at namespaces and visibility in much greater detail in Lesson 23.

Variations of defn

The basic form of defn that we just learned is by far the most common, but there are a couple of extra pieces of syntax that may be used.

Multiple Arities

First, a function can be declared with multiple arities - that is, its behavior can vary depending on the number or arguments given. To declare multiple arities, each parameter list and function body is enclosed in a separate list following the function name.

(defn my-multi-arity-fn

([a] (println "Called with 1 argument" a)) ;; <1>

( ;; <2>

[a b] ;; <3>

(println "Called with 2 arguments" a b) ;; <4>

)

([a b c] (println "Called with 3 arguments" a b c)))

(defn my-single-arity-fn [a] ;; <5>

(println "I can only be called with 1 argument"))

- Unlike the basic

defnform, each function implementation is enclosed in a list - For each function implementation, the first element in the list is the parameter vector

- …followed by one or more expressions, forming the body of the implementation for that arity

- Remember that for a single-arity function, the parameters and expressions that form the body of the function need not be enclosed in a list

Multiple arity functions are often used to supply default parameters. Consider the following function that can add an item to a shopping cart. The 3-ary version lets a quantity be specified along with the product-id, and the 2-ary version calls this 3-ary version with a default quantity of 1:

(defn add-to-cart

([cart id] (add-to-cart cart id 1))

([cart id quantity]

(conj cart {:product (lookup-product id)

:quantity quantity})))

This is one area that is surprisingly different than JavaScript because functions in ClojureScript can only be called with an arity that is declared explicitly. That is, a function that is declared with a single parameter may only be called with a single argument, a function that is declared with two parameters may only be called with 2 arguments, and so forth.

Docstrings

A function can also contain a docstring - a short description of the function that serves as inline documentation. When using a docstring, it should come immediately after the function name:

(defn make-inventory

"Creates a new inventory that initially contains no items.

Example:

(assert

(== 0 (count (:items (make-inventory)))))"

[]

{:items []})

The advantage of using a docstring rather than simply putting a comment above the function is that the docstring is metadata that is preserved in the compiled code and can be accessed programmatically using the doc function that is built into the REPL:

dev:cljs.user=> (doc make-inventory)

-------------------------

cljs.user/make-inventory

([])

Creates a new inventory that initially contains no items.

Example:

(assert

(== 0 (count (:items (make-inventory)))))

nil

Pre- and post-conditions

ClojureScript draws some inspiration from the design by contract concept pioneered by the Eiffel programming language. When we define a function, we can specify a contract about what that function does in terms of pre-conditions and post-conditions. These are checks that are evaluated immediately before and after the function respectively. If one of these checks fails, a JavaScript Error is thrown.

A vector of pre- and post-conditions may be specified in a map immediately following the parameter list, using the :pre key for pre-conditions and the :post key for post-conditions. Each condition is specified as an expression within the :pre or :post vector. They may both refer to the arguments of the function by parameter name, and post-conditions may also reference the return value of the function using %.

(defn fractional-rate [num denom]

{:pre [(not= 0 denom)] ;; <1>

:post [(pos? %) (<= % 1)]} ;; <2>

(/ num denom))

(fractional-rate 1 4)

;; 0.25

(fractional-rate 3 0)

;; Throws:

;; #object[Error Error: Assert failed: (not= 0 denom)]

- A single pre-condition is specified, ensuring that the

denomis never zero - Two post-conditions are specified, ensuring that the result is a positive number that is less than or equal to

1.

You Try It

- In the REPL, define a function that takes 1 argument, then call it with 2 arguments. What happens?

- Try enclosing the parameter list and function body of a single-arity function in a list. Is this valid?

- Combine all 3 of the advanced features of

defnthat we have learned to create a function with a docstring, multiple arities, and pre-/post-conditions.

Functions as Expressions

Now that we have learned how to define functions mechanically, let’s take a step back and think about what a function is. Think back to Lesson 4: Expressions and Evaluation where we developed a mental model of evaluation in ClojureScript. Recall how an interior s-expression is evaluated and its results substituted into its outer expression:

(* (+ 5 3) 2)

;; => (* 8 2)

;; => 16

In Lesson 4, we took it for granted that an s-expression like (+ 5 3) evaluates to 8, but we did not consider how this happened. We need to expand that mental model of evaluation to account for what happens a function is called.

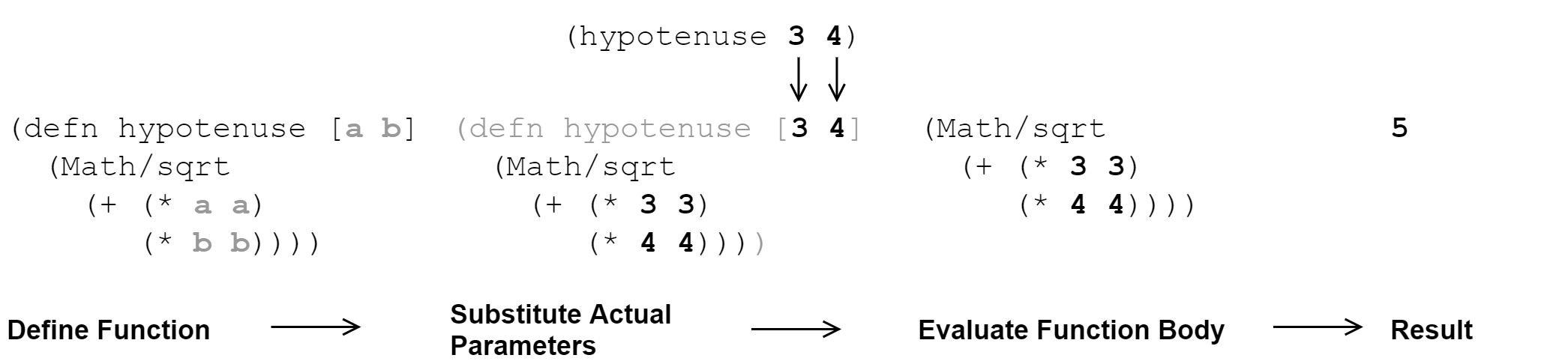

When we define a function, we declare a list of parameters. These are called the formal parameters of the function. The function body is free to refer to any of these formal parameters. When the function is called, the call is replaces with the body of the function where every instance of the formal parameters is replaced with the argument that was passed in - called the actual parameters. While this is a bit confusing to explain, a quick example should help clarify:

(defn hypotenuse [a b] ;; <1>

(Math/sqrt

(+ (* a a)

(* b b))))

(str "the hypotenuse is: " (hypotenuse 3 4)) ;; <2>

(str "the hypotenuse is: " (Math/sqrt ;; <3>

(+ (* 3 3)

(* 4 4))))

(str "the hypotenuse is: " 5) ;; <4>

"the hypotenuse is: 5" ;; <5>

- Define a function called

hypotenuse - Call the function we just defined

- Replace the call to the function with the body from the function definition, substituting

3in the place ofaand4in the place ofb - Evaluate the resulting expression

- Continue evaluation until we have produced a final value

Parameter substitution

When we think about a function as a template for another expression, it fits nicely into our existing model of evaluation. Functions in ClojureScript are a simpler concept than in JavaScript because they do not have an implicit mutable context. In JavaScript, standard functions have a special this variable that can refer to some object that the function can read and mutate. Depending on how the function was defined, this may refer to different things, and even experienced developers sometimes get tripped up by this. ClojureScript functions - by contrast - are pure and do not carry around any additional state. It is this purity that makes them fit well into our model of expression evaluation.

Closures

Although ClojureScript functions do not have automatic access to some shared mutable state by default, there is one more detail that we have to account for when reasoning about how a function is evaluated. In ClojureScript, just like in JavaScript, functions have lexical scope, which means that they can reference any symbol that is visible at the site where the function is defined. When a function references a variable from its lexical scope, we say that it creates a closure. For example, we can reference any vars previously declared in the same namespace:

(def http-codes ;; <1>

{:ok 200

:created 201

:moved-permanently 301

:found 302

:bad-request 400

:not-found 404

:internal-server-error 500})

(defn make-response [status body]

{:code (get http-codes status) ;; <2>

:body body})

- Define a var in the current namespace

- Referencing this var inside our function creates a closure over it

Since ClojureScript has the concept of higher-order functions, a function that is returned from another function can also reference variables from the parent function’s scope:

(def greeting "Hi") ;; <1>

(defn make-greeter [greeting] ;; <2>

(fn [name]

(str greeting ", " name))) ;; <3>

((make-greeter "Здрасти") "Anton")

;; => "Здрасти, Anton"

- The symbol

greetingwill refer to a var with the value ofHiwithin this namespace - Within this function,

greetingwill refer to whatever argument is passed in, not the namespace-level var - The inner function closes over the

greetingfrom it’s parent function’s scope

In this example, the function returned from make-greeter creates a closure over greeting. If we were to call (make-greeter "Howdy"), the resulting function would always substitute "Howdy" for greeter whenever it was evaluated. Even though there was another value bound to the symbol greeting outside the make-greeter function, the inner function is not able to see it because there is another symbol with the same name closer to the function itself. We say that the namespace-level greeting is shadowed by the inner greeting. We will study closures in more detail in Lesson 21 and see how we need to modify our mental model of evaluation in order to accommodate them.

Functions as Abstraction

As we saw above, functions are ways to re-use expressions, but they are much more than that. They are the ClojureScript developer’s primary means of abstraction. Functions hide the details of some transformation behind a name. Once we have abstracted an expression, we don’t need to be concerned anymore with how it is implemented. As long as it meets our expectations, it should not matter to us anymore what happens under the hood. As a trivial example, lets look at several potential implementations for an add function.

(defn add [x y] ;; <1>

(+ x y))

(defn add [x y] ;; <2>

(if (<= y 0)

x

(add (inc x) (dec y))))

(defn add [x y] ;; <3>

47)

(add 17 23) ;; <4>

- A basic function to add two numbers

- Another function for adding. It’s less efficient, but it works.

- A very opinionated function for adding. Unfortunately, it is almost always wrong.

- Call the

addfunction. All we know is that it is supposed to add our numbers.

The real power comes when we move from specific, granular function to higher levels of abstraction. In ClojureScript, we often find ourselves starting a new project by creating many small functions that describe small details and processes in the problem domain then using these functions to define slightly less granular details and processes. This practice of “bottom-up” programming gives us the ability to focus on only the level of abstraction that we are interested in without caring about either the lower-level functions that it is composed of or the higher-level functions in which it serves as an implementation detail.

Quick Review

- Define a function using

my-incthat returns the increment of a number. How would you define a function with the same name without usingdefn? - What is the difference between the formal parameters and actual parameters

- What does shadowing mean in the context of a closure?

Recursion 101

As the last topic of this lesson, we will cover recursive functions. As we mentioned earlier, a recursive function is simply a function that can call itself. We made use of loop/recur in the last chapter to implement recursion within a function. Now let’s see how to implement a recursive function using the classic factorial function.

(defn factorial [n]

(if (<= n 1)

n ;; <1>

(* n (factorial (dec n))))) ;; <2>

- Base case - do not call

factorialagain - Recursive case, call

factorialagain

This example should be unsurprising to readers with prior JavaScript experience. Recursion works essentially the same in ClojureScript as it does in JavaScript: each recursive call grows the stack, so we need to take care not to overflow the stack. However, if our function is tail recursive - that is, if it calls itself as the very last step in its evaluation - then we can use the recur special form just as we did with loop in the last lesson. The only difference is that if it is not within a loop, recur will recursively call its containing function. Knowing this, we can write a tail-recursive version of factorial that will not grow the stack:

(defn factorial

([n] (factorial n 1))

([n result]

(if (<= n 1)

result

(recur (dec n) (* result n)))))

ClojureScript is able to optimize this recursive function into a simple loop, just as it did with loop/recur in the last lesson.

Quick Review

- If you are uncertain how recursion works, go back and read from “Recursion 101”.

Summary

In this lesson, we took a fairly detailed look at functions in ClojureScript. We learned the difference between fn and defn, and we studied the various forms that defn can take. We considered the model of evaluation for functions and presented them as a means of extracting common expressions. Finally, we looked at recursive functions and saw how to use recur to optimize tail-recursive functions. While JavaScript and ClojureScript look at functions in a similar way, we made sure to point out the areas of difference so as to avoid confusion moving forward.

In practice, many functions return

nil, which is a value that denotes the absence of any meaningful value. Functions that returnnilare often called for side effects. ↩︎This code sample is intended to be a direct translation in order to illustrate the similarity between functions in ClojureScript and JavaScript. It is not idiomatic ClojureScript, and it does not take advantage of the standard library. ↩︎

Functions can be made private by declaring them with

defn-instead ofdefn. ↩︎