Lesson 25: Intro to Core Async

Asynchronous programming lives at the heart of web development. Almost every app needs to communicate with an API backend, respond to user input, or perform some other IO task without blocking the main thread. While it is entirely possible to use JavaScript’s Promise API from ClojureScript, we have another paradigm for asynchronous programming at our disposal - the core.async library. This library implements the same concurrency model as the Go programming language, and it allows us to write code as sequential processes that may need to communicate with each other.

In this lesson:

- Learn about CSP, the concurrency model behind ClojureScript (and Go)

- Think of concurrent problems in terms of processes

- Use channels to communicate between processes

Overview of CSP

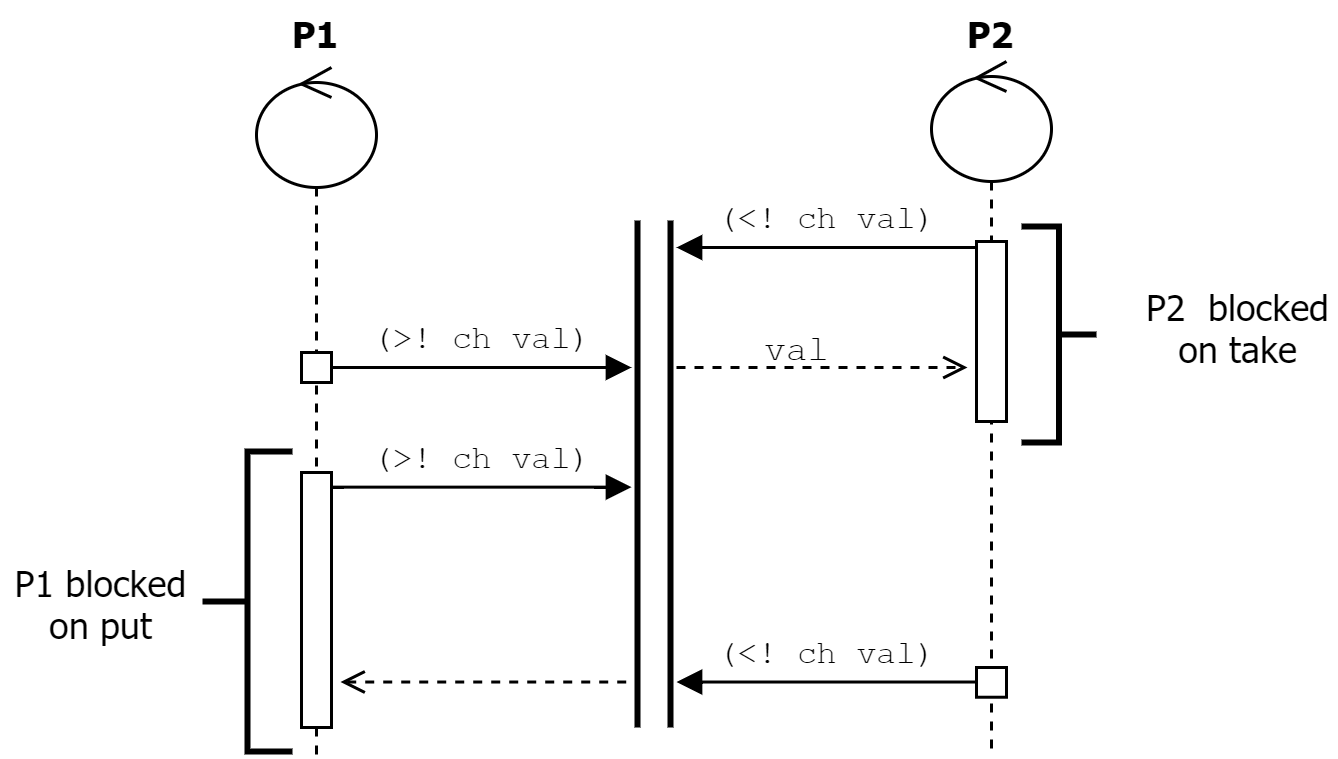

ClojureScript’s library for concurrency is based on a mathematical process calculus (concurrency model) called Communicating Sequential Processes, which was described by Tony Hoare in 1978. The basic idea behind CSP is that there are a number of independent processes that each execute some ordered sequence of steps. These processes can communicate with each other by sending or receiving messages over channels. When a process wants to read a message from a channel, it blocks until a message is available, then it consumes the message and moves on. A process can also place a message on a channel either synchronously or asynchronously. By using communication over channels, multiple processes can synchronize such that one process waits for a specific input from another before proceeding.

In ClojureScript, the core.async library provides the functionality that we need to create these asynchronous workflows in the form of the go macro, which creates a new lightweight process, chan, which creates a channel, and the operators, <! (take), >! (put), and alts! (take from one of many channels). Using only these primitives, we can create very sophisticated asynchronous communication patterns. Before diving in with core.async, let’s take a quick step back to talk about CSP.

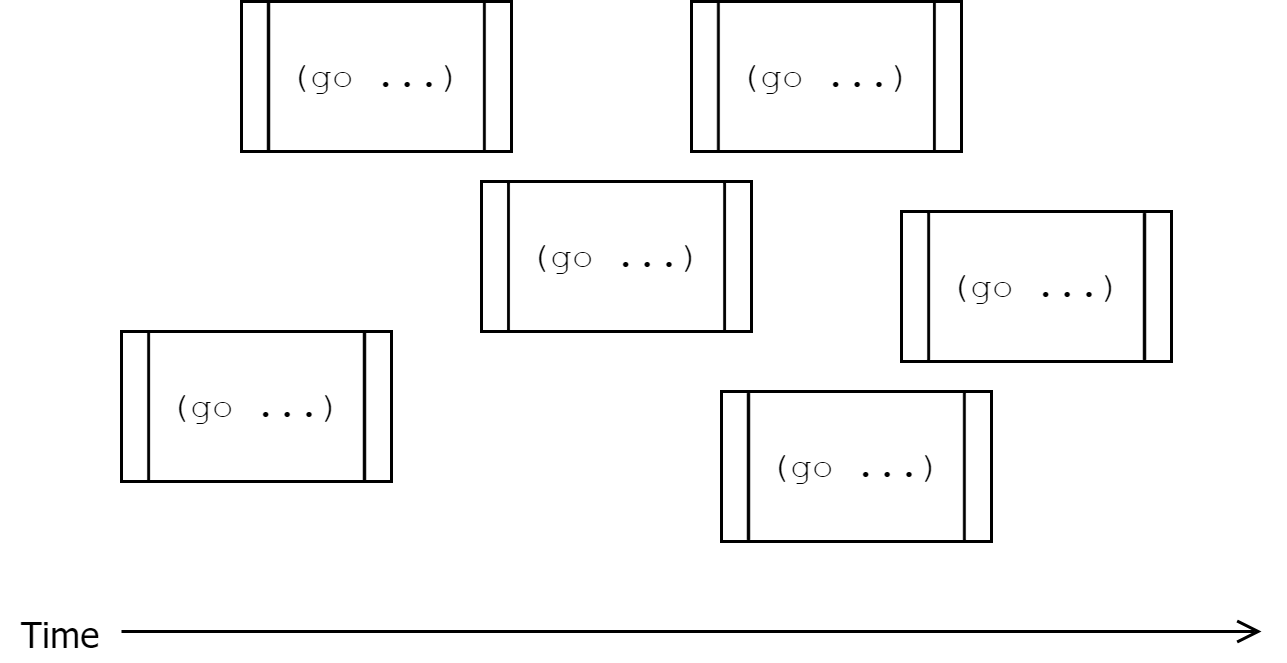

In CSP, the fundamental object is the process. A process is simply an anonymous (unnamed) piece of code that can execute a number of steps in order, potentially with its own control flow. Code in a process always runs synchronously - that is, the process will not proceed on to the next step until the previous step completes. Each process is independent of every other process, and they all run concurrently (ClojureScript is is charge of scheduling what process should run when). Finally, even though communication is a cornerstone of CSP, processes do not necessarily have to communicate with any other processes.

Concurrent Processes

Moving on from processes, the next key object in CSP is the channel1. A channel is simply a conduit that can carry values from one process to another. By default, each channel can only convey a single value at once. That is, once a process sends a value on a channel, the next process that tries to send on that channel will be parked until another process takes the value out of that channel. Additionally, trying to take a value from an empty channel will park the receiver until a value is put in. Channels can also be created with buffers that can hold up to some specified number of values that have not been taken out of the channel. Additionally, these buffers can either park producers when they fill up (which is the default behavior), or they can silently discard any new values (via dropping-buffer) or push out the oldest value in the buffer (via sliding-buffer).

NOTE

We mention that processes can park when trying to read from an empty channel or write to a full channel. From the perspective of the process, it is blocked and cannot make any progress until the state of the channel changes. However, from the perspective of the ClojureScript runtime, other processes can continue running, and the parked process can eventually be resumed if the state of the channel changes. We avoid using the language of blocking, since ClojureScript runs in the single-threaded context of JavaScript, and parking a process does not block that thread.

Synchronization with Channels

With this understanding of how processes and channels work, we are ready to dig in to an example. Let’s say that we are building an SQL query editor, and whenever the user is focused in the query input and presses Ctrl + Enter, we send off the query to a server and wait for a response. We will have one process that watches keystrokes, and another process that coordinates user input and performing a server request when necessary.

Since core.async is exposed as an official library rather than part of the core library, we need to add a dependency to deps.edn for any project in which we would like to use it:

:deps {;; Other deps}

org.clojure/core.async {:mvn/version "1.3.610"}}

Go Blocks as Lightweight Processes

In ClojureScript, we create a process using the go macro containing the block of code to execute. A simple go block could look like the following:

(go (println "Hello Processes!"))

This will asynchronously print, Hello Processes! to the console, similar to the following JavaScript code:

setTimeout(() => console.log("Hello Processes!"), 0);

We can create as many of these go blocks as we would like, and they will all run independently of each other. The interesting part comes when we introduce channels into a go block. In the next example, we read values from one channel and forward the ones that satisfy a predicate onto another channel. This is essentially a channel filter operation:

(go (loop []

(let [val (<! in-ch)] ;; <1>

(when (pred? val) ;; <2>

(>! out-ch val))) ;; <3>

(recur)))

A Filtering Process

- Read a value from

in-ch - Test the value with

pred? - Write the value to

out-ch

This example illustrates a common paradigm in core.async: we create go blocks that infinitely loop, performing the same task over and over. Just like JavaScript has its global event loop that will execute our code and callbacks, we can create mini event loops that are concerned only with a very small piece of functionality. In fact, this infinitely-looping process pattern is so common that core.async provides a go-loop macro that combines a go block with a loop. Using this macro, our code becomes:

(go-loop []

(let [val (<! in-ch)]

(when (pred? val)

(>! out-ch val)))

(recur))

To illustrate how each process runs independently, we can make use of the timeout function provided by the core.async library. This function returns a channel that closes after a specified timeout (in milliseconds). Let’s create 2 processes that each log to the console on a given interval:

(go-loop []

(<! (timeout 100))

(println "Hello from process 1")

(recur))

(go-loop []

(<! (timeout 250))

(println "Hello from process 2")

(recur))

Quick Review

- True or false? Each go block always runs to completion before any other go blocks are run.

- What is the more concise way of writing

(go (loop [] ... (recur)))?

Communicating Over Channels

Returning to the example of the SQL query editor, we could spawn a process to listen to keyboard input and emit events for all “key chords” consisting of one or more modifier keys (Ctrl, Alt, Shift, etc.) plus another key. For this, we will need to listen for keydown and keyup events and place them on channels. When we detect a chord, we place the results on another channel:

(def keydown-ch (chan)) ;; <1>

(gevent/listen js/document "keydown"

#(put! keydown-ch (.-key %)))

(def keyup-ch (chan)) ;; <2>

(gevent/listen js/document "keyup"

#(put! keyup-ch (.-key %)))

(def is-modifier? #{"Control" "Meta" "Alt" "Shift"})

(def chord-ch (chan))

(go-loop [modifiers [] ;; <3>

pressed nil]

(when (and (seq modifiers) pressed) ;; <4>

(>! chord-ch (conj modifiers pressed)))

(let [[key ch] (alts! [keydown-ch keyup-ch])] ;; <5>

(condp = ch

keydown-ch (if (is-modifier? key) ;; <6>

(recur (conj modifiers key) pressed)

(recur modifiers key))

keyup-ch (if (is-modifier? key)

(recur (filterv #(not= % key) modifiers)

pressed)

(recur modifiers nil)))))

Detecting Key Chords

- Put the key for all

keydownevents on a channel - Put the key for all

keyupevents on a channel - Keep track of any modifiers keys held down as well as the last other key pressed

- If we have any modifiers as well as a pressed key, send the chord on the

chord-chchannel - Wait for values of either

keydown-chorkeyup-chchannels - Add the key that was pressed or remove the key that was released and recur

Sending Values Asynchronously

In addition to using a go-loop that maintains state on each recursive pass, we encounter a couple of new pieces of core.async here. The first is the put! function. This function puts a value on a channel asynchronously. The normal put and take operators (>! and <! respectively) are only designed to be run inside a go block. One option that we have is to spin up a new go block every time that we want to put a value onto a channel. For instance, the keydown listener could have been written as follows:

(gevent/listen js/document "keydown"

#(go (>! keydown-ch (.-key %))))

However, this incurs some additional overhead that we may not want every time that a key is pressed. The put! function is a much cheaper option in this case. Remember that using >! will park the process, but when we are not in a go block, we do not want to wait for a channel to be ready before proceeding. We want to be able to send a value off asynchronously, knowing that it will be received by the channel when it is ready. This is exactly what put! does. Like >!, it takes a channel and a value to put on that channel. Additionally, we can supply a callback as a third argument, which will be called when the value is delivered to the channel.

Alternating Between Channels

As we mentioned in out introduction to CSP above, there is one additional function that we often use to consume values from more than one channel: alts!. Like >! and <!, alts! can only be called from within a go block. It takes a vector of channels to “listen to” and parks until it receives a value from any of them. Upon receiving a value, it evaluates to a vector whose first element is the value received and whose second element is the channel from which the value came. By checking the channel that we get from alts!, we can determine where the value came from and decide what to do with it.

One common use case is to implement a timeout by alternating between a channel that we expect to eventually deliver a value and a timeout channel that will close after a certain amount of time:

(go

(let [[val ch] (alts! [long-task-ch (timeout 5000)])]

(if (= ch long-task-ch)

(println "Task completed!" val)

(println "Oh oh! Task timed out!"))))

Adding Communication

So far, we have only a single process that is reading from and writing to channels. Let’s change that with another process that submits the query to a mocked server and updates the results area:

(defn mock-request [query] ;; <1>

(let [ch (chan)]

(js/setTimeout

#(put! ch (str "Results for: " in))

(* 2000 (js/Math.random))) ;; <2>

ch))

(go-loop []

(let [chord (<! chord-ch)] ;; <3>

(when (and (= chord ["Control" "r"])

(= js/document.activeElement query-input))

(set! (.-innerText results-display) "Loading...")

(set! (.-innerText results-display)

(<! (mock-request (.-value query-input))))) ;; <4>

(recur)))

Making a Mock Request

- Simulate making a request to a server, returning a channel that will eventually get results

- Wait for a random interval between 0 and 2 seconds to simulate latency

- Wait for key chords

- Perform a request and wait for the results before updating

results-display

Here we spin up another process that repeatedly takes key chords from the chord-ch channel, and checks to see if we have the correct chord and whether the query input is focused. If both of these conditions are met, then we simulate making a server request, and when the results come back, we update the results area. One thing to note is that (set! (-innerText results-display) (<! (mock-request (.-value query-input)))) will halt its evaluation until we can take a value from the channel returned by (mock-request (.-value query-input)). Internally, the go macro rewrites our code into a state machine, but all that we need to know is that whenever we need to park a process until a value is ready, any code that depends on that value will be deferred until after the value is delivered.

Quick Review

- Describe the difference between

>!andput! - How could we change the previous go block to time out a request after 1500 milliseconds?

Channels as Values

As we saw in the mock-request function, we can create channels anywhere in our code. We can pass them as arguments to functions or return them from functions. Although the serve the special purpose of facilitating communication between processes, they are just regular ClojureScript values.

It is a common idiom to return a channel from a function that produces some result asynchronously. Whereas in JavaScript, we would usually return a Promise (or write the function as async), we often return a channel when we intend for a function to be called from within a go block. Author and Clojure instructor Eric Normand suggests naming functions that return channels with a < prefix.2 Following this convention, our mock-request function would become <mock-request. This makes it easy to visually distinguish functions that return channels from other functions. Remember, however, that a function that returns a channel is less general than one that accepts a callback because when we return a channel, we dictate that any value eventually produced by that function must be consumed in a go block. For this reason, we should usually prefer writing functions that take callbacks if we do not know how we will eventually want to call them.

In addition to channels that simply create a channel that they will eventually put a value into, we can create some interesting higher-order channel functions. For instance, we can create a channel that merges values from any number of other channels:

(defn merge-ch [& channels]

(let [out (chan)]

(go-loop []

(>! out (first (alts! channels)))

(recur))

out))

At the beginning of the lesson, we already saw another useful higher-order channel function that filters the values in a channel to only ones that satisfy a predicate. Let’s look at one more example - a function that synchronizes 2 channels such that it waits for one value in each channel then produces a pair of [chan-1-val chan-2-val]:

(defn synchronize-ch [chan-1 chan-2]

(let [out (chan)]

(go-loop []

(>! out [(<! chan-1) (<! chan-2)])

(recur))

out))

With very simple functions, we can easily create very sophisticated asynchronous systems. Most importantly, because channels are values, we can create functions that manipulate channels in such a way that we abstract the communication patterns out of our business logic.

Summary

In this lesson, we learned about the Communicating Sequential Processes concurrency model and core.async, its ClojureScript implementation. After learning about the core concepts of CSP, we explored how go blocks create lightweight processes that run concurrently and can park when waiting to write to or read from a channel that is not ready. We talked about how channels help us communicate between processes and synchronize their state. Finally, we saw that the fact that channels are plain ClojureScript values makes it possible for us to manipulate the communication structure of our processes separately from our business logic. While core.async has the same expressive power as Promises and async/await in JavaScript, it presents a very useful way of thinking about concurrency that lends itself to SPAs, which often have multiple sequential interactions that all need to be handled concurrently.

The original formulation of CSP did not have channels. Instead, each processed had a unique name and passed messages to other processes directly. All notable implementations of CSP today use named channels to communicate between anonymous processes. ↩︎

Eric Normand’s style guide for core.async can be found at https://purelyfunctional.tv/mini-guide/core-async-code-style/ ↩︎