Lesson 6: Receiving Rapid Feedback With Figwheel

In the last lesson, we only executed one command, but we already have a basic project that will compile, and as we will see in a moment, automatically reload. Figwheel is the tool of choice in the ClojureScript community for reloading code and executing ClojureScript inside a web browser. Interactive development has been a huge priority for ClojureScript developers, and the instant feedback afforded by a tool like Figwheel delivers on making development a truly interactive experience.

In this lesson:

- Learn how interactive development is a cornerstone of ClojureScript

- Use Figwheel to compile and load it into the browser instantly

- Learn how to write reloadable code

In order to better understand how Figwheel can streamline development, let’s fire it up and see it in action. Since we generated a project using the clj-new with the figwheel-main template, it included an alias that we can use to start Figwheel with a single command.

$ cd weather # <1>

$ clj -A:fig:build # <2>

[Figwheel] Validating figwheel-main.edn

[Figwheel] figwheel-main.edn is valid \(ツ)/

# ... more output ...

Opening URL http://localhost:9500

ClojureScript 1.10.773

cljs.user=>

Running Figwheel

- Enter the project directory

- Start Figwheel

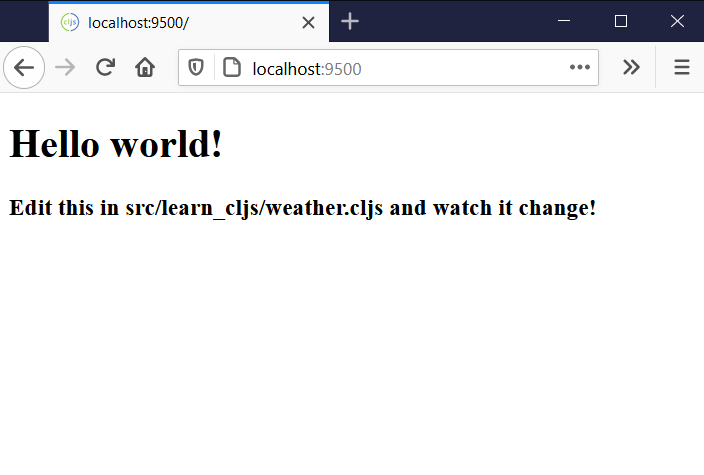

Figwheel will take a few seconds to start up and compile the existing code, but once the output indicates that Figwheel is ready to connect to our application, we can open a browser and navigate to http://localhost:9500 and see the running application.

Reloading ClojureScript with Figwheel

What happens when we start Figwheel is that it begins watching our project for any changes to the ClojureScript source files. When any of these files are changed, Figwheel compiles them to JavaScript, sends the JavaScript to the browser, and executes it.

Testing Live Reloading

Now that we have an application running with Figwheel reloading code on any change, we can open a text editor and change some of the code. The template that we used generated a single source file at src/learn_cljs/weather.cljs by default, and we will restrict the exercises in this lesson to this single file. Before we make any changes, let’s walk through the contents of this file at a high level.

(ns ^:figwheel-hooks learn-cljs.weather ;; <1>

(:require

[goog.dom :as gdom]

[reagent.core :as reagent :refer [atom]]

[reagent.dom :as rdom]))

(println "This text is printed from src/learn_cljs/weather.cljs. Go ahead and edit it and see reloading in action.")

(defn multiply [a b] (* a b))

;; define your app data so that it doesn't get over-written on reload

(defonce app-state (atom {:text "Hello world!"})) ;; <2>

(defn get-app-element []

(gdom/getElement "app"))

(defn hello-world [] ;; <3>

[:div

[:h1 (:text @app-state)]

[:h3 "Edit this in src/learn_cljs/weather.cljs and watch it change!"]])

(defn mount [el]

(rdom/render [hello-world] el))

(defn mount-app-element []

(when-let [el (get-app-element)]

(mount el)))

;; conditionally start your application based on the presence of an "app" element

;; this is particularly helpful for testing this ns without launching the app

(mount-app-element)

;; specify reload hook with ^;after-load metadata

(defn ^:after-load on-reload [] ;; <4>

(mount-app-element)

;; optionally touch your app-state to force rerendering depending on

;; your application

;; (swap! app-state update-in [:__figwheel_counter] inc)

)

src/learn_cljs/weather.cljs

- Namespace declaration

- Data structure to hold all UI state

- Declare and render a Reagent component

- Optional hook into Figwheel’s reloading process

Let’s start by making a minor change to the hello-world component. We will add a bit of extra text to it just to make sure that our changes are picked up:

(defn hello-world []

[:div

[:h1 "I say: " (:text @app-state)]])

Once we save the file, we should quickly see the browser update to reflect the extra text that we added. Next, let’s do something slightly more interesting by changing the text inside app-state to something other than “Hello World!":

(defonce app-state (atom {:text "Live reloading rocks!"}))

If we save the file again, we’ll see that nothing in the browser changes. The reason that nothing changed is that we are using defonce to create the app-state. Using defonce ensures that whenever the cljs-weather.core namespace is reloaded, app-state is not touched. This behavior can give us a large productivity boost. Consider the scenario of building a multi-page form with some complex validation rules. If we were working on the validation for the last page in the form, we would normally make a change to the code, reload the browser, then fill in the form until we got to the last page, test our changes, and repeat the cycle as many times as necessary until we had everything to our liking. With ClojureScript and Figwheel on the other hand, we can fill in the first few pages of the form then make small changes to the code while observing the effects immediately. Since the app state would not get reset when our code is re-loaded, we would never have to repeat the tedious cycle of filling out the earlier pages.

You Try

- Change the

hello-worldcomponent to render a<p>tag instead - Create a new component called

greeterthat renders, “Hello, <YOUR_NAME>” and update the call tordom/renderto usegreeterinstead ofhello-world.

Do I need an IDE?

You can edit ClojureScript in any editor or IDE that you are comfortable with. Most modern text editors have Clojure/ClojureScript plugins that will provide syntax highlighting and often parenthesis balancing. Some of the more popular editors in the ClojureScript community are VS Code, Emacs, LightTable (which is itself written largely in ClojureScript), and vim. If you prefer an IDE, Cursive is a fully-featured Clojure/ClojureScript IDE built on top of IntelliJ IDEA. Whether you decide to use an IDE or simple text editor, you can find excellent ClojureScript support.

In addition to reloading ClojureScript code, Figwheel also takes care of reloading any stylesheets that we may change as well. The Figwheel template that we used when creating this project configures Figwheel to watch any styles in the resources/public/css directory for changes. To test this out, we will open the default (empty) stylesheet and add a couple of styles:

body {

background-color: #02a4ff;

color: #ffffff;

}

h1 {

font-family: Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;

font-weight: 300;

}

resources/public/css/style.css

Upon saving the stylesheet, Figwheel will send the new stylesheet to the browser and apply it without a full page load. The ability to instantly receive feedback on any ClojureScript or CSS change can lead to a very productive workflow.

Writing Reloadable Code

Having Figwheel reload your code is a great help, but it is not magic - we are still responsible for writing code that can be reloaded without adversely affecting the behavior of our application. Later in this book, we will be building several applications on React.js and a ClojureScript wrapper called Reagent, which strongly encourage a style of coding that is conducive to live reloading, but we should still familiarize ourselves with what makes reloadable code so that we can still take full advantage of live reloading whether we are using one of these frameworks or not.

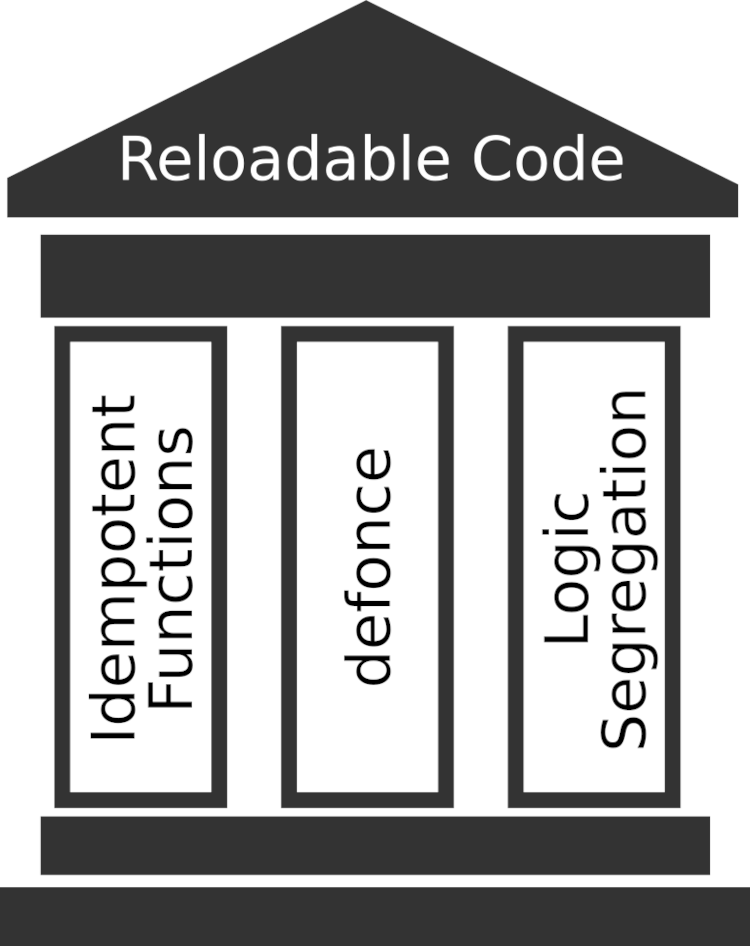

There are many considerations that go into writing reloadable code, but they essentially boil down to three key concepts, which we will consider as the “Pillars of Reloadable Code”: idempotent functions, defonce, and display/business logic segregation.

The Pillars of Reloadable Code

When we write code that holds to these three pillars, we will often find that not only do we end up with reloadable code, but our code often ends up being much more robust and maintainable as well. With that, we’ll dig into each of these pillars and how to apply them to our code.

Idempotent Functions

An idempotent function is a function that will have the same effect whether it is called once or many times. For instance, a function that sets the innerHTML property of a DOM element is idempotent, but a function that appends a child to some other element is not:

Idempotent and Non-Idempotent Functions

(defn append-element [parent child] ;; <1>

(.appendChild parent child))

(defn set-content [elem content] ;; <2>

(set! (.-innerHTML elem) content))

- Non-idempotent function

- Idempotent function

The append-element function is definitely not idempotent because the effect will be different when we call it 100 times than when we call it once. The set-content function, on the other hand, is idempotent - no matter how many times we call it, the result is going to be the same. When working with live reloading, we should make sure that any function that is called on reload is idempotent, otherwise the side effects of that code will be run many times, leading to undesirable results.

You Try It

- Write a version of

append-elementthat is idempotent and will only append the child if it doesn’t already exist. A possible solution is given below:

(defn append-element [parent child]

(when-not (.contains parent child)

(.appendChild parent child)))

defonce

When we have scaffolded a Figwheel project with the --reagent argument, the namespace that it generates uses a construct called defonce to define the application state:

(defonce app-state (atom {:text "Hello world!"}))

As we mentioned above, defonce is very similar to def, but as its name suggests, it only binds the var once, effectively ignoring the expression on subsequent evaluations. We often define our app state with defonce so that it is not overwritten by a fresh value every time our code is reloaded. In this way, we can preserve the state of the application along with any transient data while the business logic of our application is reloaded.

Another useful pattern for using defonce is to protect initialization code from running repeatedly. A defonce expression takes the form: (defonce name expr) where name is a symbol that names the var to bind and expr is any ClojureScript expression. Not only does defonce prevent the var from being redefined, it also prevents expr from being re-evaluated when the var is bound. This means that we can wrap initialization code with a defonce to guarantee that it will only be evaluated once, regardless of how often the code is reloaded:

(defonce is-initialized?

(do ;; <1>

(.setItem js/localStorage "init-at" (.now js/Date))

(js/alert "Welcome!")

true)) ;; <2>

Wrapping Initialization Code

doevaluates multiple expressions and takes on the value of the last expression- Bind

is-initialized?totrueonce the set-up is complete

In this case, we defined a var called is-initialized? that is only evaluated once and is bound to the value true once all initialization is complete. This is the first time that we have seen the do form. do evaluates each expression that is passed to it and returns the value of the final expression. It is useful when there are side effects that we want to perform (in this case, setting a value in localStorage and displaying an alert) before finally yielding some value. Combining do with defonce is a common pattern for ensuring that certain code will run only one time.

Quick Review

- While Figwheel is running, find the line in

weather.cljsthat contains(defonce app-state ...), change the text, and save the file. Does the page update? Why or why not? - Find the line in

weather.cljsthat contains[:h1 (:text @app-state)]and change theh1top. Does the page update? Why is this behavior different from changing the definition ofapp-state?

Display/Business Logic Separation

The separation of display code and business logic is good practice in general, but it is even more important for reloadable code. Recall the append-element function that we wrote several moments back when discussing idempotent functions.

Consider that we were writing a Twitter-like application and used this function to append a new message to some feed. There are a couple of ways in which we could write this code, but not all of them are conducive to live reloading. Consider the following code, which does not separate the logic of receiving a new message from displaying it:

(defn receive-message [text timestamp]

(let [node (.createElement js/document "div")]

(set! (.- innerHTML node) (str "[" timestamp "]: " text))

(.appendChild messages-feed node)))

Combining Display and Business Logic

In this example, we combine the logic of processing an incoming message with the concern of displaying the message. Now let’s say that we want to simplify the UI by removing the timestamp from the display. With this code, we would have to modify the receive-message function to omit the timestamp then refresh the browser, since our new code would not affect any messages already rendered. A better alternative would be something like the following:

(defonce messages (atom [])) ;; <1>

(defn receive-message [text timestamp] ;; <2>

(swap! messages conj {:text text :timestamp timestamp}))

(defn render-all-messages! [messages] ;; <3>

(set! (.- innerHTML messages-feed) "")

(doseq [message @messages]

(let [node (.createElement js/document "div")]

(set! (.-innerHTML node) (str "[" timestamp "]: " text))

(.appendChild messages-feed node))))

(render-all-messages!) ;; <4>

Separating Display and Business Logic

- All messages received are stored in a

defonce'd atom that will not be overwritten - The function that handles new messages is pure business logic

- The function that renders messages is pure display logic

- Perform a render

In this case, we could update the render-all-messages! function, and when Figwheel reloaded our code, the messages list would remain untouched, but the display function would behave differently, and when render-all-messages! is called, the display for all messages would be updated.

NOTE

The implementation of the above code is inefficient, since the entire list is re-rendered every time we call

render-all-messages!. In later lessons, we will use the Reagent framework to achieve similar results much more efficiently.

Quick Review

- What are the pillars of reloadable code? Why is each one of these important?

- What is the difference between

defanddefonce?

You Try

- With Figwheel running, try changing the text inside the

app-stateand saving the file. What happens? Would something different have happened if we had useddefinstead ofdefonce? - Introduce a syntax error in the code and see what happens in the browser.

Summary

In this lesson, we examined a core feature of interactive development in ClojureScript - live reloading. We used Figwheel to reload our code whenever it changed, and we looked at the principles behind writing code that is reloadable. Equipped with this knowledge, we can take our productivity to the next level and enjoy much quicker feedback than we normally get with JavaScript. We now know:

- How to start Figwheel from the command line

- How Figwheel reloads code when it changes

- How to write code that is conducive to reloading