Lesson 27: React as a Platform

In contrast to JavaScript’s multi-paradigm nature, ClojureScript promises a functional programming experience. However, we have found that as soon as we need to interact with the DOM, our code becomes… less than functional. In this lesson, we will explore how React’s declarative nature makes it a perfect platform for ClojureScript applications. We will be writing React applications, but instead of using JSX, hooks, and something like Redux or MobX for state management, we will be using ClojureScript data structures and the same tools and techniques that we have been learning about to this point.

In this lesson:

- Understand why React is the perfect platform for functional web applications

- See how React’s DOM diffing allows us to write declarative UIs

- Learn how immutability enables pure components out of the box

Functional Programming Model

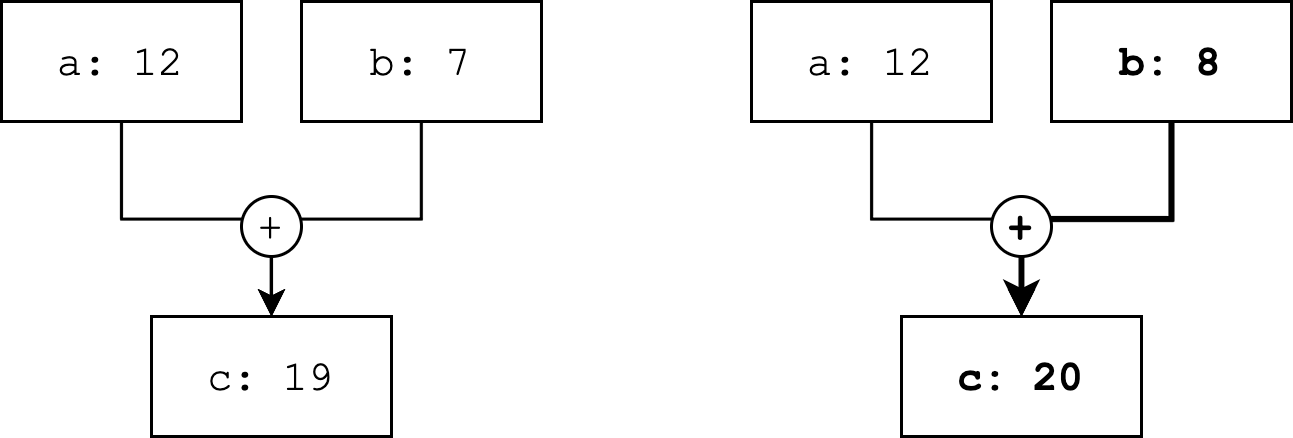

As its name suggests, React is built around the idea of reactive programming. The core concept behind reactive programming is that a program is a description of how data flows through a system. Certain values can also be computed from other values, so a change in one value may propagate to many additional values. As a concrete example, let’s think about a spreadsheet with 3 cells: A, B, and C, where C is calculated from A and B.

Reactive Spreadsheet Cells

Whenever either A or B changes, C changes as well. There may be additional values downstream that depend on the value of C, in which case the change to A or B could continue propagating. Now imagine that the final value in that chain of data dependencies is a data structure that represents the entire user interface. We have a clean and conceptually simple way to describe a UI as a computation over a reactive application state.

This reactive data model plays well with functional programming. Think back to how we modeled state updates in the previous lesson: handlers would take the current state (which was data) and a message (which was also data), and they would produce a new state. Now think about the reactive model in which a state change flows through potentially many transformations to produce a new state. If we think about the graph of those transformations being applied at a discrete moment in time, then we end up with a model of computation in which we have an application that exists as a sequence of immutable values. Each of these values is represented by a data structure that can be rendered to the DOM.

When we use React from JavaScript, we represent that data structure as JSX, and when we use ClojureScript, we use regular Clojure(Script) data structures. The fact that we do not need to think about how to mutate the DOM means that we are free from the imperative style of DOM manipulation that we have had to resort to up to this point. Since we are just transforming data, we regain all of the advantages of testability, functional purity, and determinism that has been our goal.

DOM Diffing

Our job is to produce a data structure that represents the entire application. However, re-rendering the entire DOM from scratch whenever anything changes is incredibly slow and inefficient for anything but the simplest apps. This is where React comes into play. Even if we re-compute the data structure that represents our DOM from scratch - the virtual DOM - React applies a diffing algorithm to determine what changes actually need to be made. So from our perspective, we are re-rendering from scratch on every state transition, but React is taking our virtual DOM and the previous virtual DOM and applying the necessary mutations to the actual DOM in order to bring it in sync with our virtual DOM.

As an example, we can think about a toggle switch. The toggle may be represented as a div that has an inner span with either the class toggle-on or toggle-off. We could represent it as the following:

(defn toggle-switch [on?]

[:div {:class "toggle-switch"}

[:span {:class (if on? "toggle-on" "toggle-off")}]])

When the application containing this switch first loads, let’s assume that on the initial render, this toggle gets called with on? bound to false. React will see that it had no virtual DOM before, so it will run the imperative code to create these DOM nodes with the appropriate attributes. Suppose that at some later point, the user performs an action that sets on? to true. The virtual DOM generated will go from this:

[:div {:class "toggle-switch"}

[:span {:class "toggle-off"}]]

to this:

[:div {:class "toggle-switch"}

[:span {:class "toggle-on"}]]

Even though we are returning a new data structure, React will diff the two and find that the only difference is that the class name on the span changed, so it will intelligently update only that one piece that changed. Even as we start composing many components together that may all change in some way as the app state changes over time, we can think of rendering the whole world from scratch on each change and rely on React’s diffing algorithm to calculate and make only the minimal change necessary to reconcile the actual DOM with the virtual DOM that we have declared.

Creating Fast Apps

React’s functional reactive programming model and DOM diffing are not at all unique to ClojureScript, but there is one aspect of ClojureScript that makes it much more amenable to React’s programming model: data is immutable by default. In the previous section, we talked about how we can render our application from scratch every time something changes. In a lot of cases, this is fast enough, and we can create even fairly sizeable apps that recreate an entire virtual DOM tree on every update. However - going back to the toggle case - if the toggle is part of a very large app, and its state is the only thing that changed, we do not need to re-render potentially hundreds of components.

Value Equality

We have already talked about the fact that ClojureScript’s data structures are immutable, but they also have another very useful property: value equality. This means that two data structures are considered equal if they have the same contents, regardless of whether they point to the exact same structure in memory or not. This is not the case in JavaScript. For instance, consider the following code:

const xs = [1, 2, 3];

const ys = [1, 2, 3];

xs === ys; // false

const dog1 = { name: 'Fido' };

const dog2 = { name: 'Fido' };

dog1 === dog2; // false

In terms of equality, JavaScript does not care whether two arrays or two objects happen to have the same contents or not. If they are not references to the exact same object in memory, then they are considered not equal. In contrast, ClojureScript considers data structures of the same type with the same contents to be equal. Translating the JavaScript example to ClojureScript yields a different result:

(def xs [1 2 3])

(def ys [1 2 3])

(= xs ys) ;; true

(def dog1 {:name "Fido"})

(def dog2 {:name "Fido"})

(= dog1 dog2) ;; true

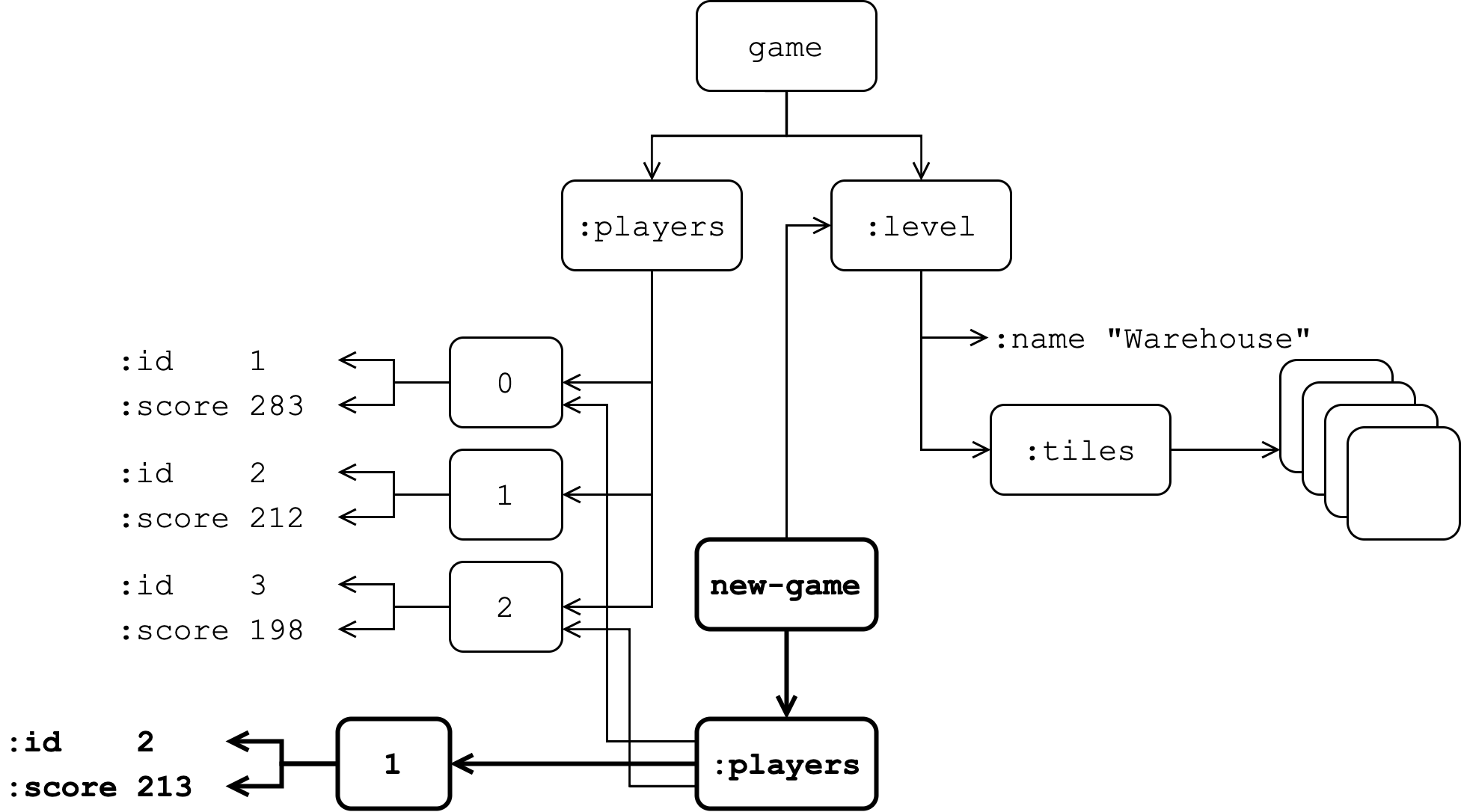

Two ClojureScript collections only differ if their contents differ. If we think about an arbitrarily nested data structure, we can see that a change to a nested property will cause its parent to no longer be equal to the parent element in the original structure. The changes will cascade all the way up to the top-level collection. However, properties that do not lie in the path from the element that changed back to the root will not be affected, and they will be equal across the original and updated structures. Let’s illustrate this with an example.

(def game {:players [{:id 1 :score 283}

{:id 2 :score 212}

{:id 3 :score 198}]

:level {:name "Warehouse"

:tiles [[:empty :empty :crate :wall-v :empty]

;; ...

]}})

(def game-new (update-in game [:players 1 :score] inc)) ;; <1>

(= (get-in game [:players 1 :score]) ;; <2>

(get-in game-new [:players 1 :score]))

;; false

(= (get-in game [:players 1]) (get-in game-new [:players 1]))

;; false

(= (get-in game [:players]) (get-in game-new [:players]))

;; false

(= game game-new)

;; false

(= (get-in game [:level]) (get-in game-new [:level])) ;; <3>

;; true

(= (get-in game [:players 0]) (get-in game-new [:players 0]))

;; true

- Update a nested property

- Everything between the updated property and the root is not equal

- Everything outside the update path is equal

Additionally, testing two data structures for equality is a relatively cheap operation in Clojure. The reason for this has to do with the fact that ClojureScript uses persistent data structures that implement structural sharing. What this means is that when we have one data structure and apply some transformation to it, the resulting data structure will only recreate the portions of the original that have changed. Any collection within the data structure that does not change as a result of the update will refer to the exact same collection in memory. When ClojureScript does its equality check, it first tests to see whether two objects are both references to the same object in memory. This is an extremely fast test, and in the case that a portion of the data structure is shared, this check can elide a much more expensive deep equality check.

Persistent Data Structures

Pure Components

In React, an instance of React.Component will always re-compute its virtual DOM when React tries to re-render it. An instance of React.PureComponent, on the other hand, will only re-compute its virtual DOM if any of its props or state are not equal to their values on the previous render. Pure components achieve this optimization by implementing the shouldComponentUpdate() method. In ClojureScript, the components that we create will behave like React PureComponents. Since each component will be backed by an immutable data structure, we will only end up re-computing its virtual DOM when we know it is necessary.

While it is possible to hand-optimize the shouldComponentUpdate() method or use immutable data and pure components when using React with JavaScript, we get these optimizations for free with ClojureScript. As we will see in the next lesson, the Reagent framework optimizes things even farther.

Summary

In this lesson, we learned how React’s reactive programming model fits well with pure functional programming practices and immutable data. We also saw how React’s virtual DOM allows us to express our UI as a data structure and let React take care of rendering efficiently. Finally, we saw how immutable data, efficient equality checks, and pure components work together to provide an optimized rendering process out of the box.