Lesson 10: Making Choices

Up to this point, we have mostly been writing code that has some starting point and progresses until it is complete.1 It has a well-defined task and must follow a well-defined series of instructions to accomplish this task. What we have been missing is the concept of a choice - being able to take a different path depending on some condition. Imagine a road that stretched for hundreds and hundreds of miles without ever intersecting with another road. If we were to drive along that road, it would be easy because we would never have to decide whether to take another route; however, the drive would also be fairly uneventful. It is the same with the code that we write: we could write scripts that simply run from top to bottom and have a clear linear execution, but then we would be missing out on the most interesting and rewarding programs.

In this lesson:

- Apply

ifandwhento make simple choices - Become familiar with the concept of truthiness and how it is defined

- Choose between multiple options with

cond

Example: Adventure Game

Text-Based Adventure Game

In this lesson, we will build a simple text-based adventure game. Adventure games are perfect for learning the concept of conditionals, since they are built around letting the user make a series of choices of how to navigate a virtual environment. So that we can focus on learning one building block at a time, we will use the author’s bterm terminal emulator library. This will allow us to focus on the core concepts of control structures without getting mired in DOM manipulation and event handling or learning a large framework.

Making Simple Choices With if And when

When we are making choices, we usually need to determine if something is true or false: is a particular checkbox selected? Is the account balance below some threshold? Does the player have some particular potion in their inventory? These kinds of questions can only have one of 2 answers - “yes” or “no”. Remember that ClojureScript works by evaluating expressions, so these questions usually take the form of an expression that evaluates to something that is either true or false. We could imagine the above questions translated to ClojureScript expressions:

;; Is the checkbox checked?

(aget my-checkbox "checked")

;; Is the account balance below a threshold?

(< (:balance account) low-balance-threshold)

;; Does the player have the potion of wisdom in their inventory?

(some #(= (:name %) "Potion of Wisdom")

(get-inventory player))

Expressions That Ask Questions

When we evaluate one of these expressions (assuming that the vars we reference are actually defined), the value will be something that we can consider to be either true or false.

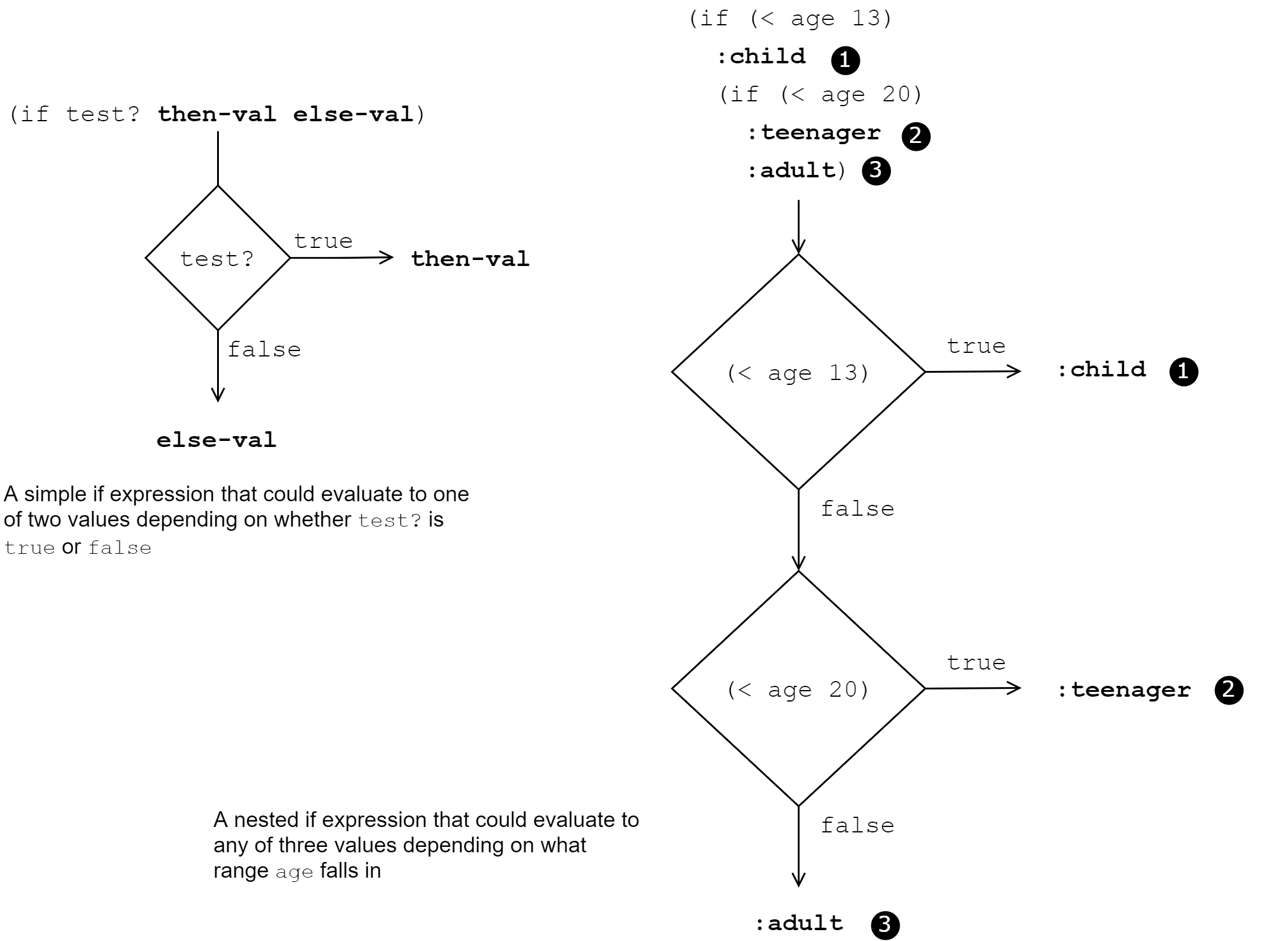

Selecting With if

We often want to make one choice when the answer is true and another choice when the answer is false - in this situation, we can use ClojureScript’s if special form. An if expression takes the following form:

(if test-expr then-expr else-expr)

if takes 3 expressions: a test, a value to use if the test is true, and a value to use if the test is false. The entire if expression will evaluate to the value of either the second or third expression depending on the value of the first expression. To use the account balance example from above, we could write the following:

(def account-status

(if (< (:balance account) low-balance-threshold) ;; <1>

:low-balance ;; <2>

:ok)) ;; <3>

- Test whether the balance is below some point

- If the test is true, evaluate to

:low-balance - If the test is false, evaluate to

:ok

NOTE: Special Forms

When we write an s-expression, ClojureScript will evaluate it as long as the first symbol in the expression resolves to the name of a function, a macro, or a special form. While the call to

iflooks just like a function call,ifis actually a special form rather than a function. We have now been writing functions for a while, and we will learn to write macros in a later lesson, but special forms are baked into the language because they are so fundamental that they cannot be implemented as a library function (or at least not efficiently). Thankfully, from our perspective as developers, we do not need to be concerned whether the specific thing that we are calling is a function, macro, or special form, since there is no difference in the way that they are called.

While the idea of an if statement should be familiar to any developer, there is a key difference between most languages’ if statement and ClojureScript’s if: in ClojureScript, if is an expression, so it always evaluates to a specific value. In an imperative language like JavaScript, the if statement usually makes a choice between which code branch to execute. The actual if statement does not yield a value. For instance, the following is not valid JavaScript:

// This will throw a SyntaxError

const answer = if (someCondition) {

'Yes';

} else {

'No';

}

JavaScript Ifs Are Not Expressions

However, JavaScript does provide the ternary operator, which is an expression. ClojureScript’s if expression is very similar to JavaScript’s ternary operator, but there is one less piece of syntax to deal with!

const answer = someCondition ? 'Yes' : 'No';

…But Ternaries Are

In JavaScript - as in most imperative languages - we use if statements to perform side effects such as conditionally setting a variable, prompting the user for input, or manipulating the DOM. In ClojureScript, we usually use the if expression to decide between two values. The entire expression will take the value of either the then expression or the else expression. Selecting between more than 2 values can also be accomplished by replacing either the then or else expression with another (nested) if expression.

Conditional Evaluation

Take care, however, as deeply nested if expressions can be difficult to read and can usually be replaced with a cond, which we will learn about later in this lesson.

Quick Review

- Explain the difference between

ifin JavaScript and ClojureScript - How would you write an

ifexpression that - given 2 numeric values,aandb- would evaluate to"greater"if a > b,"less"if a < b, or"same"if they are equal?

Conditional Evaluation With when

Closely related to if is the when expression. We can think of it as an if without an else expression:

(when test-expr some-value)

When the test expression is true, the entire expression evaluates to the value given, and when the test is false, the expression evaluates to nil. In fact, when is just shorthand for an if where the else expression is nil:

(if test-expr some-value nil)

The two common use cases for when are to transform a value only when it is non-nil and to perform some side effect when a certain condition holds true. For the first case, we often see code like the following:

(defn conversion-rate [sessions] ;; <1>

(let [users (user-count sessions)

purchases (purchase-count sessions)]

(when (> users 0) ;; <2>

(/ purchases users))))

- Define a function that gets the ratio of purchases to users

- Use

whento prevent division by zero

For the second case, we will often want to perform some DOM manipulation or other side effect only in a specific case. For instance, we may want to pop up an error message when we receive a server error from a back-end API:

(when (< 499 (:status response))

(show-error-notification (:body response)))

Applying if and when

Considering the example of the adventure game, we can use use an if expression to determine what to do after prompting the user for a yes/no question. Let’s take a quick step back to discuss the overall architecture of the game. We will represent the entire game as a map where the keys are the name of each state and the values are maps that represent a specific screen. The general shape of our game data structure is below:

We will represent our game as a collection of states with rules that determine how to move between states when the user makes some decision:

{:start { ... }

:state-1 { ... }

:state-2 { ... }

:state-3 { ... }

:win { ... }}

Our game will start with the user in a spaceship at Starbase Lambda, and their goal is to uncover the location of the Tetryon Singularity. They will issue simple commands as well as answer “yes” or “no” questions.

Each state in the game (which we filled in with { ... } above) will contain a :type, :title, :dialog, and :transitions. The type determines what sort of state the game is in - e.g. :start, :win, or :lose - title and dialog determine what we display onscreen, and the transitions determine which state the user should transition to depending on the choice that they make. For example:

{:type :start

:title "Starbase Lambda"

:dialog (str "Welcome, bold adventurer! You are about to embark on a dangerous "

"quest to find the Tetryon Singularity.\nAre you up to the task?")

:transitions {"yes" :embarked,

"no" :lost-game}}

Example game state

When the user is in this state, we will print the title and dialog to the screen and prompt them for input. If they type “yes”, we’ll advance to the :embarked state; otherwise, we’ll move on to the :lost-game state.

Instead of walking through scaffolding a new project, we can checkout a skeleton project from the book’s github repo, which already has the necessary dependencies configured in deps.edn as well as some basic markup and styles. We will be working from Git tag lesson10.1.

Prompting for Input

The first thing that we will want to do is display the title and dialog from whatever scene the user is currently in and prompt them for input. We’ll handle the input later, so for now let’s just think about how we can display the scene. The bterm library that we are using provides several useful functions for controlling output:

print- prints a screen to the terminalprintln- prints a screen to the terminal with a trailing newline characterclear- clears any existing output from the terminal

With this in mind, let’s think about how to display the scene. We always want to print the title and dialog, but we should also indicate if they have won or lost the game. In this case, we can display either, “You’ve Won!” or “Game Over”. To accomplish this, we can first test the type of the current scene and only display the end game message if the type is either :win or :lose:

(when (or (= :win type) ;; <1>

(= :lose type))

;; Display message ;; <2>

)

- Check if user is in an end-game state

- Perform the side effect of printing some message

Furthermore, we want to use a different message depending on whether the user has won or lost. We can accomplish this with if:

(io/println term

(if (= :win type) "You've Won!" "Game Over"))

The if expression will evaluate to either “You’ve Won!” or “Game Over” depending on the value of type

Putting these pieces together with the printing of the title and dialog gives us something like this:

(defn prompt [game current] ;; <1>

(let [scene (get game current) ;; <2>

type (:type scene)]

(io/clear term)

(when (or (= :win type) ;; <3>

(= :lose type))

(io/print term

(if (= :win type) ;; <4>

"You've Won! "

"Game Over ")))

(io/println term (:title scene)) ;; <5>

(io/println term (:dialog scene))

(io/read term #(on-answer game current %)))) ;; <6>

Prompting for input

- This function takes the entire game data structure and the current scene

- Create 2 local bindings with

letthat we will use in the rest of the function - Conditionally print an end-game message

- Determine which message to print

- Print the title and dialog no matter what the scene type is

- Handle whatever the user types using the on-answer function that we are about to write

Handling Input

Now that we have taken care of the display side of things, we will want to handle user input. In the previous snippet, we passed control to the on-answer function when the user entered an answer. This function, like prompt, is passed the entire game data structure as well as the key identifying the current scene; however, it is also passed the string that the user entered at the prompt. Using this information, we need to determine which scene to display next then prompt the user for input once more. Here is the skeleton of what this code should look like:

(defn on-answer [game current answer]

(let [scene (get game current)

next ;; TODO: determine the next state

]

(prompt game next)))

To start, we only need to handle responses of “yes” or “no”. Since we are only deciding between 2 options, a single if expression will suffice:

(if (= "yes" answer)

(get-in scene [:transitions "yes"])

(get-in scene [:transitions "no"]))

You Try It

There is another type of game state that we need to handle = :skip, which has the following shape:

{:type :skip

:title "..."

:dialog "..."

:on-continue :next-state}

Add another conditional to the on-answer function that will proceed to the next state regardless of what the user enters. A possible solution is given below:

(defn on-answer [game current answer]

(let [scene (get game current)

next (if (= :skip (:type scene))

(:on-continue scene)

(if (= "yes" answer)

(get-in scene [:transitions "yes"])

(get-in scene [:transitions "no"])))]

(prompt game next)))

Truthiness and Falsiness

Before continuing, let’s take a brief step back to talk about the concept of truthiness in ClojureScript. The test expression that we pass to if or when can be an actual boolean value - true or false - but it does not have to be. As in JavaScript, we can pass any value as the test. Even if it is not a boolean, the language will either consider it to be “truthy” and pass the test or “falsy” and fail it.

Unlike JavaScript, which has a number of special cases that it considers to be falsey, ClojureScript follows a very simple rule: false and nil are falsy, and everything else is truthy.

ClojureScript’s Truthiness Rule

falseandnilare falsy, and all other values are truthy.

Quick Review

- What is the value of

(if TEST "Truthy" "Falsy")for each of the following values for “TEST”:truefalse"false"""0niljs/NaN[]

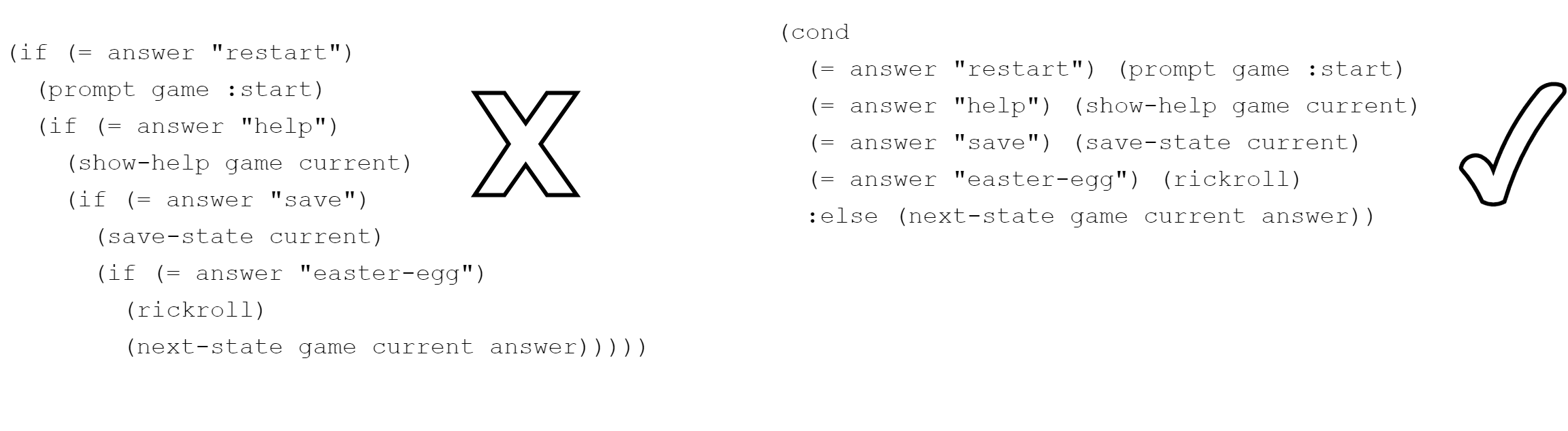

More Complex Choices With cond

With if and when, we have all that we technically need to handle any sort of decision-making that we need to do in code. However, we are often faced with cases in which if would be awkward to use. Consider adding more commands to our game so that the user could type “restart” to go back to the beginning or “help” to display the commands that are available. As we add more options, we would have to keep nesting more and moreif expressions - like using a pocket knife to carve a wooden sculpture, it could work, but the result would not be pleasant.

Enter cond and its cousins, condp and case. cond takes some expression and any number of test/result pairs, and the entire expression will evaluate to the “then” expression that comes after the first test that is truthy:

(cond

test-1 then-1

test-2 then-2

;; ...

test-n then-n)

The structure of cond

It is idiomatic to use :else as the test expression for a “fall-through” value if no other test is truthy. Remember that only false and nil are falsy, so the keyword :else will always be truthy and will satisfy cond if no prior test does. Thinking about the additional commands that we would like to add to our game, this would be much simpler using cond.

Replacing Nested If With Cond

Repeated Tests With condp

If this was as good as we can do, it would be a significant improvement, but we can still simplify things further with a more focused variation of cond called condp. Like cond, condp allows us to choose from among a number of options, but if there is a lot of common code in each of the test expressions, condp can usually help us factor it out. In our case, we test the value of “answer” for equality with some string in every test expression.

This is a great case for condp, which takes 1) a binary predicate – that is, a function that take two arguments and returns a boolean value, e.g. = 2) an expression to use as the right-hand side in every test, and 3) any number of left-hand test-expression/result pairs. It can also take 4) an optional default value to use if none of the prior tests were truthy.

(condp pred expr

test-expr-1 then-1

test-expr-2 then-2

;; ...

test-expr-n then-n

default-expr)

The Structure of condp

For every test expression/result pair, it applies the predicate to the test expression and the other expression and evaluates to the first result value whose test expression passed the predicate. On paper, this can be confusing, but seeing an example can help clarify things, so here is our text-based menu re-written using condp:

(condp

= ;; <1>

answer ;; <2>

"restart" (prompt game :start) ;; <3>

"help" (show-help game current)

"save" (save-state current)

"easter-egg" (rickroll)

(next-state game current answer)) ;; <4>

- Use the

=predicate function to test each option - Pass

answeras the right-hand side in every test - Each clause will be tested as

(= "restart" answer) - Provide a default expression if every prior test fails

Compared to our original implementation with nested if statements, this version using condp is quite succinct and readable. For this reason, condp is widely used to test multiple values when the full flexibility of case is not required.

Quick Review

- Using

condto write some code that will evaluate to:poswhen a given number is positive,:negwhen it is negative, and:zerowhen it is exactly zero - Write code that will do the same thing using

condp

Summary

In this lesson, we learned what are usually referred to as the branching control structures. We learned that, in contrast to JavaScript and other imperative languages, these structures are used as expressions that choose between values rather than imperative statements that direct the flow of execution. We also looked at ClojureScript’s concept of truthiness and how it is simpler than that of most other languages. We can now:

- Choose between two values using

if - Conditionally evaluate code using

when - Simplify multiple-choice options using

condandcondp

Even though they function a little differently in ClojureScript than in other languages, these branching mechanisms are one of the most fundamental building blocks that we need to write applications. Next, we will look at the other class of control structures - loops.

We have come across some code samples that have used conditionals because they are almost unavoidable for any interesting program. ↩︎